Table of Contents

Why the welfare of zoo-housed animals matters

Why should we care about the welfare of animals housed in zoos? Because everything that progressive zoos do starts with promoting good animal welfare!

Some may argue that in an ideal world we would not keep animals in zoos, limiting their freedom, just for humans to gawp at. They have a point! Good zoos justify their existence on four key goals: conservation, educational opportunities, research and recreation.

Assessing and promoting animal welfare is fundamental to achieving each of these goals of good zoos, and indeed promoting welfare should be the fifth goal. (Rose & Riley, 2022)

Why do Zoos exist?

Good zoos justify their existence primarily for conservation reasons.

Tragically, animals in the wild face many threats to their existence – especially habitat loss, either directly (e.g. through deforestation or human encroachment), or indirectly through habitat alteration due to climate change.

Animals are also poached by humans for food, medicine or the pet trade. The work done by zoos can help to save species, many of which are endangered or threatened with extinction.

To achieve this conservation goal, good zoos may:

- work in situ (e.g. in protecting the animal’s natural habitat)

- engage in research such as understanding the needs of animals, their genetics, disease and other veterinary concerns, as well as research on reproductive biology

- engage in captive breeding to maintain a genetically viable captive population, occasionally reintroducing animals to boost declining populations in the wild.

To bolster conservation, good zoos also provide educational opportunities for people to learn about animals, increase their knowledge of biodiversity and learn what actions to take to protect it.

For children in particular, these early experiences may have lifelong consequences for their attitudes to animals and their desire to value and protect nature. To encourage people to visit zoos, the visits must be enjoyable.

Indeed, the public paying to visit zoos supports their existence financially, and so along with conservation, research and education, recreation is the fourth goal of good modern zoos. Here we argue that it is fundamental to assess and promote animal welfare to achieve each of these goals of good zoos, and indeed that promoting welfare should be the fifth goal.

Humans cannot provide good welfare

Despite the importance of good welfare, we must be clear that as humans, we cannot provide animals with good welfare – for it is not something that we can give to another creature (Brando & Buchanan-Smith, 2018).

Animal welfare is how the animal responds to the social and physical environment in which they live. Humans caring for animals decide upon and provide these conditions – the size of the enclosure and its furnishings, the other animals who may live in the enclosure, the type of food, its presentation, the timing of feeds and other features in the indoor enclosure such as temperature, lighting and humidity.

The provision of these conditions that humans can control are termed resource “inputs” – but how animals respond is termed “outputs”. It is widely accepted that it is the way animals feel in response to their nutrition, health, physical environment and their behavioural interactions that determines their welfare (Mellor et al, 2020).

Animal welfare from a range of perspectives

Why we care about animal welfare depends somewhat on our perspective. From the perspective of animals in zoos and those who care for them, from the perspective of zoo visitors, those in zoo education, zoo researchers and conservationists, and from those managing zoos and Chief Executives. All have reasons to care. All can contribute to better lives for animals, and potentially themselves, and their business.

The importance of animal welfare from several perspectives

The animals'

The animals'

The animal caregivers'

The animal caregivers'

The zoo visitors'

The zoo visitors'

The zoo educators'

The zoo educators'

The zoo researchers' and conservationists'

The zoo educators'

The zoo managers'/Chief Executives'

The zoo managers/Chief Executives'

By having institutional approaches, and a culture of care, where the wellbeing of the animals is at the centre, everyone benefits. It benefits the animals of course. The staff may have increased wellbeing improving staff retention, and visitor numbers increase, both contributing to the zoos’ financial viability. This can lead to increased educational benefits, and allow conservation demands to be met during a time of accelerating extinctions.

How should we care? Assessing the welfare of zoo-housed animals

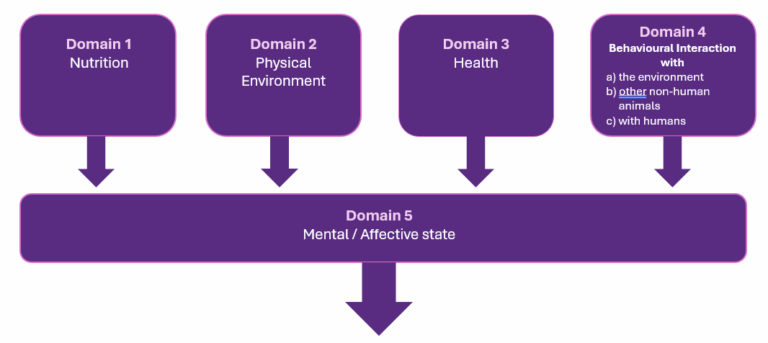

Having convinced you, we hope, of the reasons why we should care about the welfare of zoo-housed animals we must now think about how to care. Animal welfare is notoriously difficult to assess. The most currently accepted framework for understanding animal welfare is called The Five Domains.

The Five Domains Framework has four physical/functional domains: nutrition, physical environment, health, and behavioural interactions and in turn these feed into the affective state, the way the animals feel. As human caregivers, we can input into all the physical/functional domains by providing:

- nutrition that gives the animals well balanced diets to support their physical and mental health

- appropriate physical environments to allow animals to perform their natural behaviours

- appropriate conditions for healthy living and veterinary care when needed

- opportunities for the right types of interactions with the environment with both same species companions, and with individuals of different species (including humans!)

But whilst we may be able to quantify inputs relatively easily, it is considerably more difficult to quantify the animals’ outputs. An identical captive condition may allow for very good welfare for one individual but the same condition may not be appropriate for another individual. For example dominant and subordinate animals may have different opportunities to use the same resource input, and young and old may have very different needs.

Difficulties in quantifying animal welfare

Animal welfare assessment in zoos is complicated because assessments of welfare:

- Must cover the full range of biological and mental needs of the animal

- Require much time, many resources, and trained staff to conduct them

- Mean that management priorities may need to be shifted

- Require investment to learn about welfare and the resources available for conducting welfare assessments

- Often cover a diverse number of species with many varying needs and limited research on their life history and behaviour

- Need to be validated and have reliable welfare indicators for all species

- Need to fit into the regular work routine

- Require investment in collating information from the many staff and departments involved

- Require expertise to interpret the data and to implement effective interventions if needed.

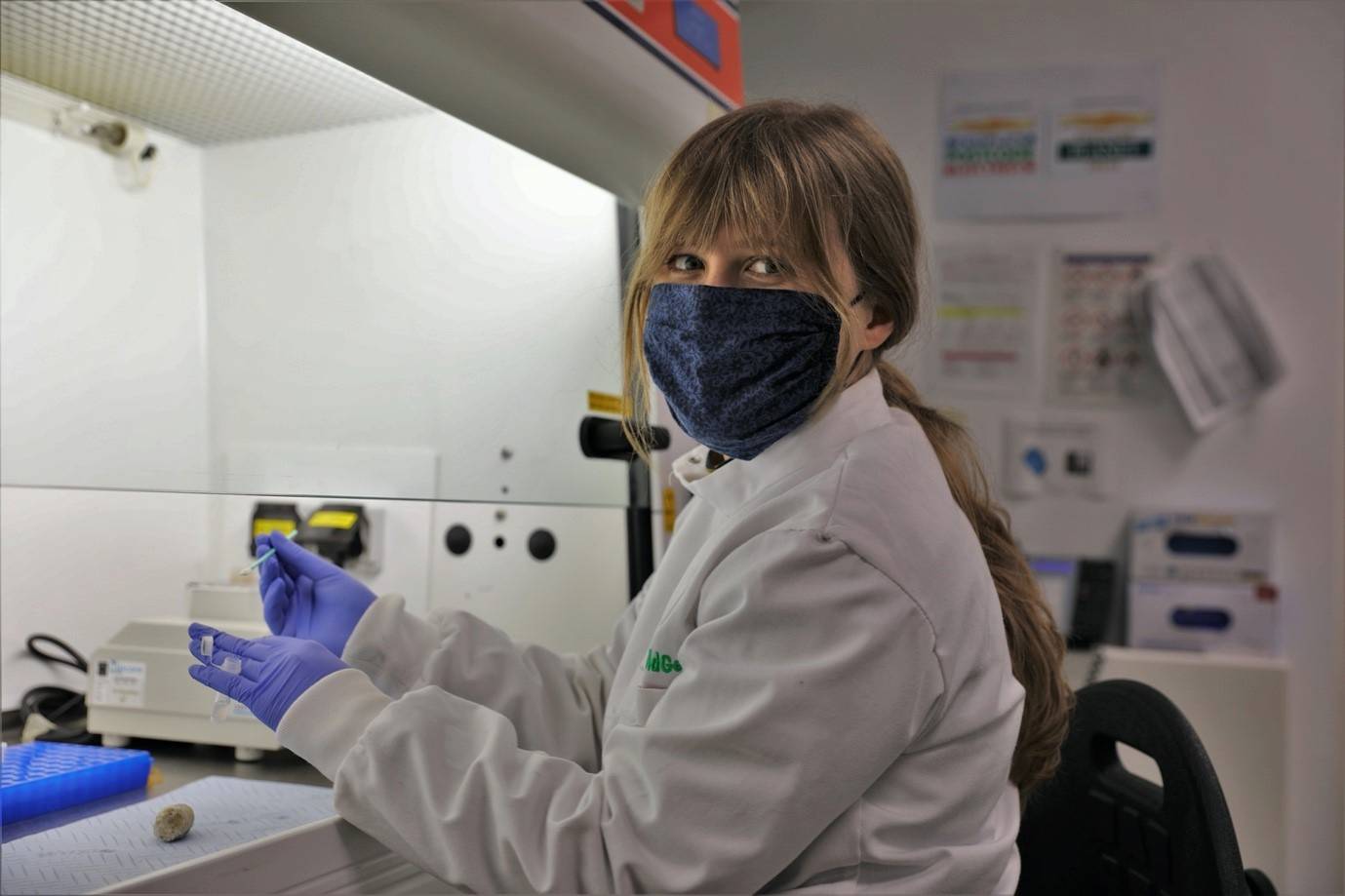

Through collaborative research, RZSS and the University of Stirling have addressed these difficulties through the development of the Standardised Welfare Assessment Tool (SWAT) and Behaviour and Environment Evidence-Base (BEEB). These resources make the welfare assessment process reliable, efficient, and provide clear and effective outcomes.

Many approaches to welfare assessment

Our welfare assessment tools are focused on the widely accepted structure of the Five Domains framework, considering resource “inputs” and animal “outputs” (Mellor et al, 2020). However, other prominent frameworks exist with many strengths and benefits. These frameworks include the Universal Animal Welfare Framework (Kagan, Carter & Allard, 2015), the Animal Welfare Assessment Grid (Justice et al, 2017) and the European Welfare Quality® project (Blokhuis, 2008).

However, one important aspect that none of these frameworks address is the continuous nature of welfare. These frameworks do not apply the cyclical nature of the day, week, and seasons to the approach of assessing welfare, nor do they address how welfare may be affected through different life stages.

A framework that has been proposed, which aims to address this, combining principles from the Welfare Quality® project and Five Domains, is the 24/7 across the lifespan approach to welfare assessment. This 24/7 approach emphasises having a holistic method to welfare that considers the natural history of an animal and how the context of a zoo environment affects natural cycles.

Brando & Buchanan-Smith (2018) are clear it is not an animal welfare assessment though. The approach aims to map out and research whether the needs and wants of captive animals are being met 24/7, across the lifespan. Though some frameworks encourage that rhythms be considered for aspects of welfare like the changing diet composition throughout the year, none goes as in-depth to suggest that welfare is continuous on multiple time scales and should be assessed as such.